Preference laundering is a phenomenon in which advocacy groups, policymakers, and influential non-profit organizations manipulate truth under the guise of acting in the common, popular, or scientific interest. One example of preference laundering is alive and well in gun violence research and activism as described in this

article.Preference laundering in this field involves selectively presenting data and policy narratives to construct public support for predetermined “gun safety” policy objectives, which are often backed by academia, unaccountable bureaucrats, authoritarian politicians, and corporate journalists pushing their preferred narrative. Public health researchers and advocacy groups frequently employ questionable methodologies, including the misrepresentation of defensive gun use statistics, the selective exclusion of declining violent crime trends, and the conflation of lawful gun ownership with criminal activity.

As OSD writes:

If you want to predict what kinds of studies will get published, look at which studies will get rewarded. Incentives determine outcomes, because they define the direction in which an ecosystem’s selective pressures will push. And to understand which studies get rewarded, you have to understand how they get used. What demand are they fulfilling?

Academia is theoretically a disinterested search for truth. And sure, many of the people working within it do genuinely approach their work that way. But whatever accolades and funding they’ll be rewarded with for their statistical rigor pale in comparison to the returns on having a study hit big in the mainstream press. In that domain, statistical rigor doesn’t matter. What matters is a splashy headline.

These tactics create the illusion of a scientific consensus of an “epidemic of gun violence” while marginalizing viewpoints that challenge this false narrative and diverting from genuine issues surrounding the prolific use of firearms such as male suicides.

The same tactic is evident in bicycle infrastructure advocacy with similar rhetoric towards an “epidemic of traffic violence”, where preference laundering distorts public perceptions regarding cyclist safety and infrastructure requirements. This process is particularly evident in the advocacy for segregated or "protected" bicycle infrastructure, which is frequently misrepresented as a universal benefit for cyclists often under the guise of “feeling safer” and “for all ages and abilities.” Instead of prioritizing cyclist safety and usability, these initiatives often serve non-profit industrial complex ideological objectives, such as demonizing car use, reinforcing an anti-motorist agenda, and advancing “urbanist” policies.

Many of these infrastructure projects rely on poorly designed studies and misleading data to create the illusion that “protected” bikeways are safer and preferred by cyclists.

In reality, such infrastructure often increases dangers for cyclists, particularly at driveways and intersections, and promotes the idea that roads are only for automobiles despite the 130+ year history of traffic law.

Bob Shanteau's "The Marginalization of Bicyclists"

Note on the Restoring Sensible Cycling Advocacy Series:

The League of American Bicyclists (LAB), PeopleForBikes, Streetsblog, and fiat academics (most notable public health researchers who provide much of the “knowledge” and Science™ in this field) exemplify how preference laundering operates within the sphere of bicycle advocacy.

The League of American Bicyclists

Historically, the League of American Bicyclists (LAB) was a staunch advocate for cyclists’ rights to use existing roads under equal legal standing with motorists. However, this organization underwent ideological capture shifting from a group for and by cyclists to a K-Street lobbying group for managerial class elites, urbanists, wokies, and climate crisis hysterics.

The League’s original mission departed and was even demonized within the organization after a board coup and instead aligned itself with preference laundering efforts that prioritize unsafe segregationist bicycle infrastructure over equitable and safe access to public roads.

The Ideological Capture of the League of American Bicyclists

(The article about human factors and how they contribute to solo “protected” bike lane cyclist crashes as promised at the end of Why “Protected” Bicycle Lanes Violate the Principle of the Space Cushion" is postponed for another time. That article’s research is taking far longer than expected.

LAB’s Bicycle Friendly Community (BFC) program plays a significant role in enforcing bicycle segregation preference laundering. Municipalities seeking BFC recognition, which function as a grading system for how well a municipality aligns with modern League ideology, are encouraged to implement extensive bikeway and infrastructure projects, often at the expense of cyclist safety and efficiency. Instead of improving road-sharing policies, empowering motorist and/or cyclist education, and clearing up traffic law misconceptions, the BFC program pushes for hazardous segregated infrastructure, creating the illusion that municipalities are acting in the best interest of cyclists when, in reality, they are sidelining their rights in favor of a predetermined agenda.

As Fred Oswald pointed out:

The BFC rating criteria, the applications submitted and LAB’s feedback are kept secret from LAB members. If LAB revealed this information, we could easily see the overwhelming emphasis of the BFC program on segregated bikeways and the lack of concern for safety and fairness to cyclists. However, we can infer these problems by looking at what is asked on the application and by examining the communities getting the award

If the BFC evaluation process were equally divided between the five areas (engineering, education, encouragement, enforcement/adjudication, and evaluation/planning), then “engineering” (which mostly has involved building segregated facilities) could produce only 20 percent of the score. In addition, at least half of the engineering score should go towards non-bikeway facilities (e.g., pavement surface maintenance, roadway traffic signal actuation, bike parking, public transit access, ‘single track’ trails, recreational facilities (e.g., velodromes or BMX tracks), and even winter maintenance of shared-use paths).

In other words, even ignoring the serious safety problems that might remain in a “balanced” BFC evaluation process, segregated bikeways should count for no more than 10 percent of the total score. However, we know of NO communities that without segregated facilites that have gotten this award. It’s obvious that BFC rewards segregation.

The main motivations behind those running the program seem to be (1) fear and hatred of auto traffic; (2) a fanatic belief that bicycles will save the world from the evil automobile; (3) the belief that bicycle facilities help sell bikes. While the first two goals above may be worthwhile (without the fanaticism) and we have no objection to the selling bikes, this extreme form of advocacy coupled with a zealous “ends justify the means” approach, can be deadly and harmful to the cause.

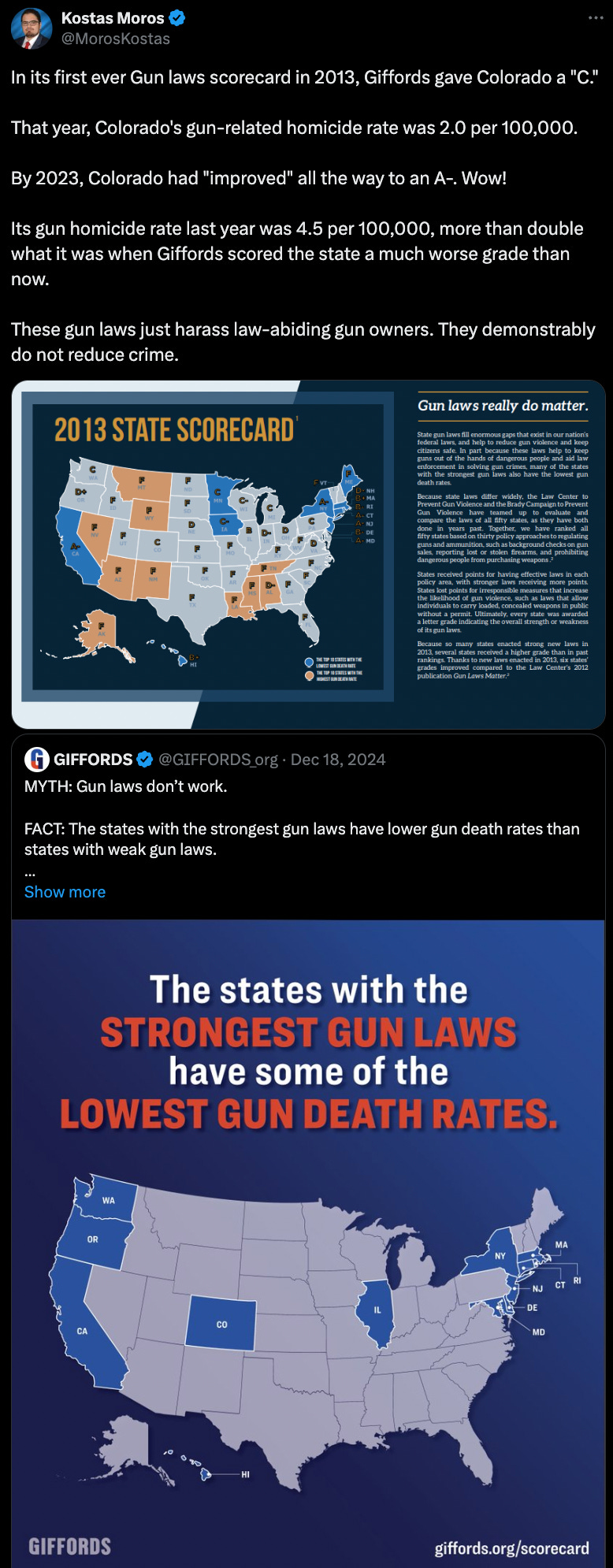

A similar trend occurs in the “gun violence” prevention domain with Gifford’s “gun law scores,” and their lack of correlation with an increase in gun control laws and a reduction in firearm homicides in Colorado - state colonized by both out of touch East Coast-based anti-2A and “pro bicycling” organizations.

PeopleForBikes

PeopleForBikes, formerly Bikes Belong, is another national advocacy group that influences bicycle policies through its funding, lobbying efforts, and public relations campaigns. The organization presents itself as a pro-cyclist entity but often aligns with corporate and governmental interests that prioritize expanding infrastructure projects over cyclist autonomy and safety.

Follow the Grift: People For Bikes

“There is no swifter route to the corruption of thought than through the corruption of language”

PeopleForBikes has been instrumental in preference laundering by promoting unsafe “protected” bikeways through selective data interpretation, misleading visuals, and flawed studies. The organization manipulates data to support its infrastructure-focused advocacy, ignoring or downplaying the risks associated with “protected” bikeways.

One example of this manipulation can be seen in John Allen’s PeopleForBikes Interprets Boulder Data, where the organization misrepresented crash data to make the case for more separated bicycle infrastructure. In this study they selectively emphasized statistics that supported their position while ignoring key safety concerns—such as increased intersection conflicts—creating the illusion that “protected” bikeways were inherently safer.

Furthermore, PeopleForBikes Transforms Michigan Street Indianapolis with Photoshop exposes how the organization used altered images to mislead the public about the effectiveness and safety of bike lane designs. This deceptive visual representation made it appear as though newly installed “protected” bikeways dramatically improved conditions when, in reality, they introduced new hazards, such as right-hook conflicts and reduced cyclist visibility at intersections where car-bike crashes are common. In A First Look at the New Study Promoted by PeopleForBikes, People For Bikes endorsed “research” that used flawed methodologies to conclude that “protected” bikeways reduced car-bike crashes. The study failed to control for crucial factors such as pre-existing safety conditions, cyclist behavior, and traffic flow changes, making the results unreliable as a justification for widespread implementation of “protected” infrastructure. Another case, PeopleForBikes Praises Flawed Figueroa Bikeway Design, highlights how the organization supported an unsafe “protected” bikeway in Los Angeles (often a homeless encampment these days more than a bike anything) despite clear evidence that it created dangerous conditions for cyclists. The bikeway's design placed cyclists in conflict zones with turning and crossing vehicle and pedestrian crossings, yet PeopleForBikes ignored these issues in favor of promoting a false narrative of increased safety.

PeopleForBikes’ also have a City Ratings system, which ranks municipalities based on their supposed bike-friendliness similar to the League of American Bicyclists’ Bicycle Friendly Program. The ratings assess factors such as the presence of “protected” bikeways and “low stress” network connectivity but nothing on their safety or whether the municipality they grade has any issues with discriminatory bicycle traffic law. Their methodology also pressures local governments to conform to a narrow, pre-approved model of bicycle safety that ignores the concerns of experienced cyclists who advocate for vehicular cycling.

By selectively using flawed research, misleading imagery, misinterpreted data, and a biased ratings system, PeopleForBikes plays a key role in bicycle segregation preference laundering—manufacturing support for infrastructure for their industry buddies but which compromises cyclist safety. This process pressures municipalities to adopt “protected” bikeways without critically assessing their effectiveness or the risks they introduce.

Streetsblog

Mark Gordon’s Streetsblog is a propaganda outlet that advocates for urbanist transportation policies, more often than not presenting a one-sided perspective that favors “protected” bicycle infrastructure, public transit, the CA High Speed rail grift, and an anti working class and anti-motoring agenda. They’re funded by non-profit industrial complex heavy hitters such as The Summit Foundation, Transit Center, and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

The Streetsblog Files Part I of ?

Through hard-hitting reporting and insightful commentary, we make complex conversations about transportation reform accessible, emotional, and urgent. Our goal is to empower our readers with the perspective, inspiration, and resources they need to dismantle the structural forces that result in car dominance, both at the level of policy and in our cultur…

While promoting safer streets and alternative transportation is a commendable goal, Streetsblog routinely marginalizes perspectives that challenge its agenda. It frequently dismisses evidence-based critiques of bike lane safety, disregarding studies that highlight the dangers of cycle tracks at intersections and the increased risk of collisions due to unpredictable right-of-way conflicts. They even sometimes promote unsafe door zone bicycle lanes and then wonder why a bicyclist died using such a hazardous lane.

Fountain of Death

“The new bike lane is welcome - and does make riding Fountain safer,” wrote Joe Linton of Streetsblog last St. Patricks´ day in a news roundup of alternative transportation in the Los Angeles area.

Capitalizing on A Bicyclist Fatality

Last week Ethan Boyes, a record-breaking professional track cyclist, was killed while cycling in the Presidio of San Francisco, a former military post in the shadows of the Golden Gate Bridge, now operated by the National Park Service (NPS) as part of Golden Gate National Recreational Area (GGNRA). The U.S. Park Police, the entity which has jurisdiction…

Streetsblog frequently prioritizes ideological commitments over sound traffic engineering. By disregarding the expertise of engineers (who are also susceptible to ideological capture) and objective safety analyses, Streetsblog actively contributes to preference laundering by promoting the erroneous notion that “protected” bikeways are the sole viable solution for cyclists.

Fiat Academia & Epidemiology

Fiat academia, a concept introduced by Dr. Saifedean Ammous in his book The Fiat Standard, highlights the phenomenon of knowledge production financed by fiat money government grants and ideological commitments to political interests masquerading as “science.” Preference laundering flourishes in this environment, manipulating public opinion to justify predetermined agendas, as exemplified in fields such as climate science, gun violence research, and of course here in bicycle safety and segregation dogma.

A notable aspect of preference laundering in the context of “protected” bicycle infrastructure is the concept of “motornormativity” and “car brain” which can be viewed as an overapplication of critical theory to transportation policy. (Paging

)Of course, it’s impossible to bring up the topic of fiat academia and bikeway studies without mentioning the flawed Why cities with high bicycling rates are safer for all road users by academics Wesley Marshall and Nicholas Feranchak. This study, or more specifically the news releases and media articles citing the abstract of the study are used as proof that segregated or “protected” bikeways are undoubtedly safe.

“Safe for all road users”

“This paper provides an evidence-based approach to building safer cities,” begins the conclusion of the study, “Why cities with high bicycling rates are safer for all road users” a study conducted by academics Wesley Marshall and Nicolas Feranchak. Published in 2019 in the

But both of these “studies” only scratch the surface of the grift in academia and in particular the role of the field of epidemiology, worthy of a slight detour.

Epidemiologists, as

notes in his excellent lecture The Excesses & Errors Of Epidemiology I frequently identify associations between exposures and diseases without establishing a direct causal link, potentially leading to exaggerated assessments of the risks associated with certain substances. Another significant issue Briggs notes is the misuse of exposure as a proxy for dose, in other words mere exposure to a substance does not necessarily imply a harmful dose. Epidemiological studies often conflate these concepts, leading to erroneous conclusions about risk levels. Additionally, the field tends to overlook uncertainties in data collection and analysis. Factors such as inaccurate self-reporting in questionnaires or misdiagnoses can introduce substantial uncertainties, which are frequently disregarded, resulting in overconfident assertions about health risks.In the case of bicycle and transportation studies, epidemiology dominates pro bicycle segregation, anti-car, and general urbanist knowledge production. Car use is seen as disease as opposed to something with benefits and drawbacks. Bicycle usage on public roads is seen as inherently dangerous and an example of someone exposed to a dangerous situation regardless of behavior by any of the involved parties. M. Kary’s 2014 Unsuitability of the Epidemiological Approach to Bicycle Transportation Injuries and Traffic Engineering Problems paper provides a scathing critique of how fiat academics, mainly in the field of epidemiology, use flawed methodologies to justify “protected” bikeway projects, making it a prime example of preference laundering.

One of the major errors in epidemiological studies on bicycle infrastructure Kary notes is diversion bias, where the effects of infrastructure changes are evaluated in a way that fails to account for how traffic shifts in response. Kary highlights the example of Vancouver, where turn prohibitions were introduced to mitigate the right book hazards of cycle tracks at intersections. However, this merely redirected turning motor traffic elsewhere, creating new hazards at nearby locations conveniently left out of the scope of the study. Such studies only measured safety outcomes on the cycle tracks themselves while ignoring the systemic risks created elsewhere. This allowed the researchers to claim a net safety benefit for “protected” infrastructure without addressing the full consequences, misleading policymakers and the public as to the safety claims of segregated or “protected” bicycle infrastructure.

Many bikeway studies Kary noted conflate statistical significance with actual safety improvements similar to what Marshall and Feranchak did in their Why cities with high bicycling rates are safer for all road users study. Kary critiques studies that claim “protected” bikeways reduce injuries but fail to control for confounding variables like cyclist behavior, road conditions, or intersection design. Some even go as far as using arbitrary adjustments to input data to achieve desired results. A glaring example is a study by one of Anne Lusk’s studies, which adjusted data with an ad hoc parameter without testing its validity. Such manipulations create an illusion of scientific rigor while ensuring the study aligns with predetermined policy objectives. Because these studies are “peer reviewed” and mere morals (non-academics) can seldom critique articles published in journals, these studies go on as new “knowledge” and “truth.”

Epidemiological studies often categorize all bicycle-related injuries together rather than analyzing the specific dangers introduced by different types of infrastructure. Kary points out that some studies recommend cycle tracks based on aggregated injury data, without differentiating between minor falls and severe collisions. This broad-brush approach leads to misleading conclusions that favor “protected” infrastructure while ignoring the engineering hazards introduced, such as conflicts at driveways, turning vehicle interactions, and door zone crashes

These methodological flaws are not just errors—they are part of a broader system of fiat academia-funded preference laundering. As Saifedean Ammous argues in The Fiat Standard, academic research is increasingly dictated by centralized funding mechanisms rather than intellectual merit. When public health institutions, government grants, and advocacy groups with a vested interest in urban redesign fund research, the studies they produce overwhelmingly support the expansion of “protected” bicycle infrastructure, regardless of the actual safety outcomes .

By selectively using flawed methodologies, omitting critical variables, and designing studies to confirm predetermined conclusions, academia plays a crucial role in laundering the preference for “protected” bikeways. This manufactured consensus then justifies policy decisions, marginalizing dissenting views from traffic engineers, experienced cyclists, and critics of cycle track designs. The result is the entrenchment of infrastructure that may not actually improve safety but serves the ideological goals of urban planners and advocacy groups .

By promoting these flawed studies, advocacy groups create an illusion of scientific consensus that enables policymakers to justify bike lane expansion as a universal good and safe, despite clear evidence that such infrastructure often makes cycling more hazardous.

Knowledge production relies commitment to the scientific method, ensuring that understanding is built upon empirical evidence and rigorous analysis. However, this process is compromised by preference laundering, where biases are disguised as objective findings, leading to distorted public discourse and policy decisions. In the context of bicycle advocacy, preference laundering has allowed ideological narratives from activists to masquerade as neutral, prioritizing their goals over genuine cycling safety.

Furthermore, the influence of fiat money in research funding can create perverse incentives, prioritizing studies that align with their own interests over those driven by genuine scientific or popular inquiry. Bicycle advocacy groups, often backed by government grants or foundation money with predetermined agendas, are incentivized to produce research that confirms preferred policy outcomes rather than engaging in rigorous analysis that might challenge these assumptions.

I like the reference here to bikes. I think I'll share this one too!

There is a bill up this year to try and do the heavy vehicle hazard fee at the local level. You seen?