The Ideological Capture of the League of American Bicyclists

How America's Oldest and Most Prolific Bicycling Organization Ceased Advocating in the Interests of Safe and Effective Cycling Practices

(The article about human factors and how they contribute to solo “protected” bike lane cyclist crashes as promised at the end of Why “Protected” Bicycle Lanes Violate the Principle of the Space Cushion" is postponed for another time. That article’s research is taking far longer than expected.)

Ideological capture refers to the process by which an institution or organization becomes dominated by a replacement ideology at the expense of its original purpose, mission, or values. This can occur when a group with a strong ideological commitment takes control of an institution and redirects its resources and organizational goals to serve the replacement ideology.

Key examples are what’s happened to the American Psychological Association in the field of clinical psychology with its embrace of bonafide racism masquerading as “anti-racism”, in academic publishing, in the medical profession surrounding the rise of so-called “gender-affirming care,” and even with formerly reputable publications such as Scientific American who now peddles pseudoscience and political activism. The journalism profession isn’t even immune.

The same happened in bicycling advocacy.

Initially grounded in principles of safety, education, and equality, bicycling advocacy in the United States once largely emphasized the cyclist's right to the road as a driver of a vehicle. But the advocacy for bicyclists’ rights to the road as drivers of vehicles has seen a significant transformation over recent decades substituted by a replacement ideology that’s in tension with the original one. In bicycling advocacy this change is evident in none other than with the League of American Bicyclists, the nation’s oldest, largest, and most influential cycling advocacy group.

The Various Rises and Falls of LAW

Much of this history on LAW/LAB came from Bill Hoffman’s history page on LABreform.

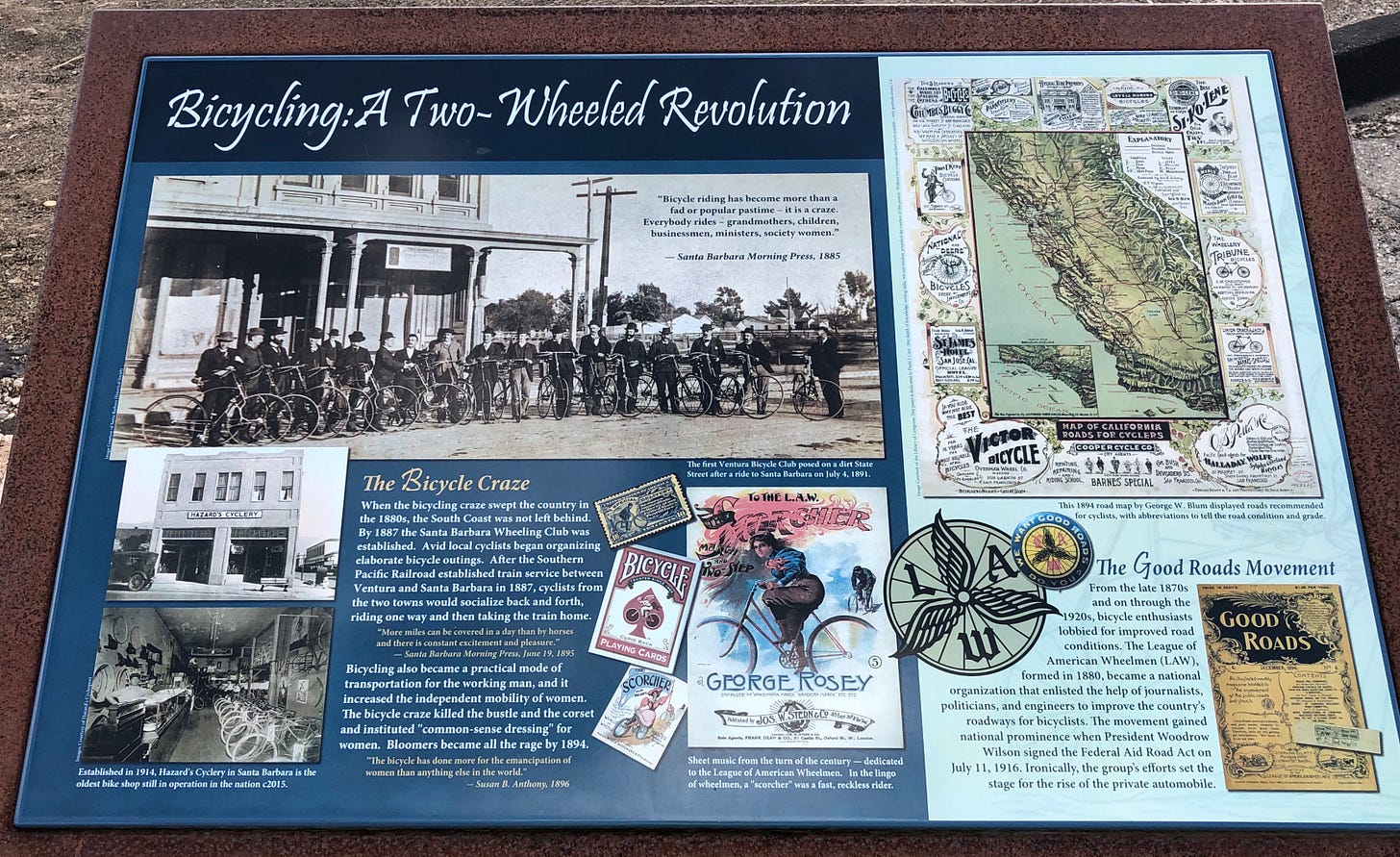

Bicycling advocacy originally sought to secure equal rights for cyclists as drivers of vehicles, highlighting their common-law right to travel on public roads. In the United States this started in the late 1800s with the League of American Wheelmen (LAW), which is now known as the League of American Bicyclists (LAB).

LAW were also early pushers for something Americans take for granted: paved roads. It was LAW’s members, who consisted of mostly urban cyclists however that spearheaded the beginning of road improvements along with rural residents with equal concerns. During the genesis of LAW, motor vehicles were a rare oddity as were paved roads. Deemed “The Good Roads Movement,” this eventually led to modern paved road and the typical road building agencies such as the now bloated and inefficient Federal Highway Administration along with state DOTs.

Back then too, it was the bicycle that was the disruptive form of transportation during an era where the streets were primarily used for walking and by animal-driven wagons. The chaos was so bad in New York City in the late 1800s in part due to cyclists at the time called “scorchers” that William Phillips Eno, as discussed in Karen Karabel’s My Bike or a Two-Ton Land Missile, created the first model traffic law which created a set of rules of movement for vehicle drivers and another one for pedestrians. Eno’s principles remain the foundation for all modern traffic law today enshrined in state statutes and in the country’s model traffic code the Uniform Vehicle Code.

Cycling soon lost to motoring, especially in rural areas and between small towns where moving goods by motor vehicle was significantly faster and more practical for people’s travel needs. Cities too saw a change with many embracing public transit in the form of streetcars, buses and some with subways but also saw growth in the popularity of the automobile. With that automobile use was coupled with serious injuries and deaths as contextualized in the Traffic Violence Epidemic Series leading to (motor vehicle) driver licensing laws, registration, insurance requirements, and a long list of traffic laws pertaining to drivers of motor vehicles. In various jurisdictions, cyclists faced bans or laws that required them to not operate as vehicle drivers and there’s traces of this period all over modern traffic codes in the form of far to right (FTR) laws, bans on certain surface streets, and mandatory bike infrastructure use laws. LAW often fought against these laws. Bob Shanteau described these laws and changes in The Marginalization of Bicyclists. By 1930 the authors of the UVC declared bicycles were no longer vehicles yet bicyclists still had the rights and duties of drivers of vehicles. That came only a few short years after a LAW victory which originally defined them as vehicles. Much of the confusion and inconsistencies both in traffic law and in popular understanding of cycling including the many myths discussed in Traffic Ignorant People Online could easily be argued to be traceable to this era.

LAWs political power eventually waned although there were brief spurts of growth in the Great Depression and during WWII rationing. In LAW’s place rose significant cultural and political power behind motoring, often deemed Motordom, which more often than not wanted the country’s public roads made exclusive for motor vehicle use and essentially saying “to hell” with the general right to travel by any non-motorized means. By the end of WWII, with the United States’ unprecedented post war boom and the rise of suburban development, LAW’s power and influence was less than background noise. The use of motor vehicles grew and the bicycle was delegated to a mere children’s toy. LAW didn’t reemerge in full until the bike boom of the 1970s. The bike boom was largely spearheaded by increased fuel prices, the rise of the modern Malthusians environmental movement thanks in large part to the US going “temporarily” off the gold standard unleashing the modern fiat era. During this era cities and road building agencies attempted to embrace cycling though building off-road side paths, bicycle lanes, and even the first “protected” bicycle lanes such as ones “protected” by parked cars and wheel stop in Davis CA. As a City of Davis site explains, “It was the first time that a lane for the preferential use of bicyclists had been designated as part of an existing roadway meant for vehicles.” (Whoever wrote that is ignorant of the fact that bicycles are vehicles.) The parking and wheel stop “protected” bicycle lanes in Davis were eventually removed or the lanes were modified with dedicated bicycle signals after in the words of that site they “didn’t prevent conflicts with turning vehicles.”

With the rise in bicycling and special infrastructure intended for bicycling, the LAW rose again in prominence fighting for properly designed bicycle infrastructure in accordance to actual engineering principles. LAB also fought against laws that chipped away at bicyclists as drivers of vehicles. It was then the infamous John Forester, easily the most lied about and most misunderstood cycling advocate rose to fame.

A Brief Forester Interlude

Entire pieces consisting of thousands of words a piece can be written on Forester but for this purposes of this piece, this will be a short introduction to the man and where he fits into LAW history.

Forester, a polymath British transplant to California and an accomplished industrial engineer had been a long time cyclist who brought with him the idea that bicyclists are vehicle drivers and should have the same rights and duties on the road which he deemed “vehicular cycling,” a term long propagandized and misunderstood by bike lane activists long before the rise of the modern Cluster B(ike) activist. That was a tradition that died quickly in the US as the bicycle diminished in use over the years while LAW waned but was still somewhat intact when Forester left the UK. It’s still seen in the book CycleCraft by British cyclist John Franklin. (Similarly, these rights are under threat too in the UK, as they too are largely starting to embrace segregated/”protected” cycling lanes)

Forester’s first main gripe that contributed to his rise to fame was a law requiring cyclists in Palo Alto use sidewalks which are pedestrian-only facilities purely inappropriate for cycling due to the various safety hazards. He fortunately eventually got this law repealed using the basic principles of traffic engineering which allowed him to start knocking out other such discriminatory laws. He critiqued the new “standards” that were emerging in California for bikeways pushed UCLA “academics” and the state DOT.

He eventually cemented himself high in ranks of the respawned LAW where he developed the organization’s bicycling safety education programs along with writing his popular book Effective Cycling.

He also took to the pages of the era’s prominent cycling magazines which unlike current abominations contained useful and informative articles such as this one penned by Forester.

There he identified the issue well over half a century ago:

Social reactions which have already been acted out in tentative steps could well destroy cycling as we know it. This has happened because there are more cyclists, but also because short-sighted enthusiasts have promoted the cause of cycling in ways that have long range detrimental effects.

He even recognized the common-law right to travel.

Besides fighting specific laws, we can carry on a general fight to maintain the street and highway system as a public utility open to all users if they do not render it unsuitable for other users. You may recognize Uncle Tom-ism in this, but the fact is that we are an uninfluential minority. We haven't the political clout to grab more than our share; we can only receive our share by the proper policy of a fair share for all. Legal precedent and economics will support us. A longstanding right existed in England and emigrated to the US: freedom of travel on the public highway. This right has been regulated only to the extent of protecting other users' similar rights.

And instead of demanding special safe spaces for bicyclists at the expense of other road users recognized not either bicyclist or motorist are always occupying the same space.

Not even motorists use all the road all the time. It makes sense to allocate the available roadway to each user as he needs it, rather than have unique paths for each class of user. This is sharing for the common good, at lowest cost to everybody. To reestablish the road-sharing principle, we need to convince people that it makes sense in general, and we have to convince them that we cyclists are legitimate members of the using community. This is going to take some doing, given the course of US traffic history since 1920 and our actions of the last year or two.

The differences between cycling safety before and after Forester’s rise is stark as John Schubert notes:

Without Forester’s innovative instruction, bicyclists of the 1970s, including those who considered themselves safety advocates, simply didn’t have the vocabulary to talk about how a bicyclist’s operating characteristics would interact with a given facility design, to produce a crash. They certainly had little notion that a bicyclist’s own behavior could make him safer.

Amazingly enough the typical modern bike lane activist and traffic “engineer” to this day still lacks such vocabulary.

Forester also helped start the California Association of Bicycling Organizations (CABO) which still exists today.

The LAB’s Leadership and Governance Coups

By the late 1970s, LAW moved close to the swamp where it could be closer to the political powerhouse of the country but waned again in the 1980s to the point of being insolvent. By 1994, the organization changed its name to the League of American Bicyclists (LAB) and with better cashflow they moved to an office on K Street. But they also increasingly focused on “reforming” their educational programs largely stripping them to the point where Forester revoked their right to use his materials.

It was in the 1990s where the governance structure of the LAB began to change too to push out actual grassroots cyclists and to replace them with a broader-scoped yet utterly centralized governance of bike lane, anti-car, and cycling adjacent activists. In hindsight, this was probably a long time coming as with most “revolutions” and coups. Needless to say, LAB faced criticism from some members who felt that its board had become increasingly insular and unaccountable. This was a departure from the now almost century-old structure, which emphasized a strong connection between the organization and its membership base. Such “professionalization” and centralization of the organization reduced transparency and limited the ability of ordinary members to influence the direction of the organization. This change escalated further with an attempt in the late 90s to change the board structure from one selected by the membership to one appointed by League insiders that was unsuccessful only after membership pushback. While that attempt flopped but the new “leadership” managed to chip away over the years at the organization’s bylaws slowly getting most of what they originally wanted.

By the early to mid 2000s this transformation was well underway. Originally, only a fraction of the board’s members were appointed with the rest voted in by the membership, then they slowly expanded number of positions appointed via sneaky bylaw changes. These changes led to incremental expansions of the total number of board position while also increasing proportions of those positions being appointed to the board meaning less and less were voted by the actual membership. By 2003, the governance transformation was completed sidestepping the cyclists interested in the organization’s original missions leading to an exodus of former members and the rise of LABReform.

The End Results of LAB’s Transformation

LAB went from protecting the rights and duties of cyclists as drivers of vehicles, pushing back against unjust and discriminatory bike laws, and slowing down the infiltration of dangerous “cycling infrastructure” to being a Washington lobbying swamp creature focused on platitudes over principles.

LAB replaced this all with an obsession on “increasing mode share” or “more butts on bikes,” along with expensive and radical transformations of the country’s streets via so-called Complete Streets programs, road diets, and an infiltration of hazardous “bicycling” infrastructure. Their education program was much watered down too. This all came while Woke ideology took the US by storm which also has touched the LAB’s work in nearly every dimension.

But perhaps the greatest example of the LAB’s ideological capture was their “Bicycle Friendly Communities” (BFC) program which consists of glorified participation trophies to cities and states for their apparent friendliness to legitimate cycling interests. If a city or other jurisdiction has hazardous door zone bike lanes, right hook magnet “protected” bike lanes and/or even continues to have discriminatory bike traffic laws on the books they’ll get the award provided they play nicely with LAB.

Over at LABReform the authors summarized the BFP savagely.

BFC has given its highest award to Portland, OR despite (or perhaps because of) its reckless program installing bike lanes in dangerous places. What makes it worse is that Oregon laws require cyclists to use these hazardous facilities. Chicago, which has many dangerous door zone bike lanes, has a BFC award despite falsifying the apparent sizes of cars & trucks depicted in scale drawings in its Bike Lane Design Guide, making them appear to be 20% smaller. See one of the drawings from the Design Guide with the vehicles re-scaled to the correct size. Chicago gives this irresponsible advice about door zone bike lanes: “Keep track of traffic behind you so you’ll know whether you have enough room if you must swerve suddenly out of the ‘Door Zone’.” What they should say is simply “Stay out of the door zone.” If a bike lane is in the door zone, it is too dangerous to use. Many other award recipients also have hazardous segregated facilities. Indeed, having segregated facilities seems to be a requirement for receiving an award. Even restricting cyclists’ right to the road is not a problem for BFC.

Another prominent example of a BFC participation trophy gone wrong is the organizations anointing of Fort Collins, Colorado which maintains a ban on cyclists on the city’s main street, College Avenue for part of its alignment through the city. Colorado, also deemed “bike friendly” has a law on its books, not touched by LAB or local groups in Colorado (also ideologically captured by segregation and “protection” dogma) that prohibits bicycling on a street if a segregated bicycling facility is located within a certain distance of the street. In the case of College Ave, the Mason Trail provides that parallel route but since it’s behind much of the city’s main commercial corridor which includes several bicycle shops, a BRT line, and a railroad, access to these properties is difficult and intrusive for cyclists. Reversing such a ban would be relatively easy on civil rights and right-to-travel grounds but without the “credible” deep-pocketed bicycle lobbying groups such as LAB, that prospect remains a pipe dream.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, LAB even flopped on their life long mission to help fight cyclists’ unjust court cases after they’d be accused as Keri Cafferty for violating “unimaginary laws” or for cycling safely but against the unjust and discriminatory cycling laws present in many jurisdictions. These cyclists were were targeted and made examples in the legal system. Prominent cases such as Reed Bates in Texas, Cherokee Schill in Kentucky, Eli Damon in Massachusetts (second article here) took the bicycling advocacy domain by storm. But the League was nowhere to be seen electing to sit out of providing any of their legal backing. Their cowardly “defense” is still live on their own website although the dozens of comments from actual cyclists condemning the decision were removed after they revamped their website.

LAB began to also push flawed bike safety studies such as the Every Bicyclist Counts study which was likely the capstone of the ideological capture. Largely pushed by the President at the time, Andy Clarke LAB shifted toward promoting protected bike lanes and shared-use paths, often described as “facilities-first” advocacy. This shift undermined principles of safe and legal cycling often labeling it as dangerous and only for the “strong and fearless.” By prioritizing physical infrastructure over education and empowerment, LAB shifted to promoting designs that marginalize cyclists to unsafe lanes and intersections prone to conflict with motor vehicles marketed as “infrastructure” for cyclists.

This facilities-first approach pandered to public demand for infrastructure without adequately considering the engineering and behavioral flaws that can arise. LAB, under Clarke’s leadership, ignored or downplayed evidence that bicycle driving strategies, rather than segregated facilities, best ensure cyclists' safety and integration into traffic instead perpetuating dangerous cycling practices and designs. LAB lent credibility to policies that prioritized political expediency over robust safety and education-based advocacy.

LAB largely continues this push to this day.

In Sum

The ideological capture of the League of American Bicyclists represents a cautionary tale for single-issue advocacy organizations. Their shift from grassroots cycling advocacy focused on education, safety, and legal equality to a largely segregation-first approach driven by political parasitism left a void in sensible and principled bicycling. LAB’s transformation highlights the need for vigilance in preserving the core values and missions of advocacy groups to ensure they continue to serve their intended constituencies rather than becoming pawns for parasitic ideological movements. It seems too late to reverse course for LAB but a return to principles-based advocacy grounded in safety, equity, and engineering soundness is essential for reclaiming the legitimacy, integrity, and effectiveness of cycling advocacy in the United States.

Follow the Money. Exec Dir Bill Nesper now leads a staff of 17 full timers. All of who are eligible for professional advancement by jumping to either in government or consultant firms, big buck positions predicated on gear mongering and unrealistic dogma about bicycling saving American cities, promoting Equity, keeping oceans from boiling, whatever.

Ebikers have done far more, faster, to get Americans out of their cars than all the bullshit infra pushed by the Advocacy Industrial Complex. With LABs help bicyclists will be run over by faster, heavier, wider E-things driven by ignorant riders who bring their motorist self-entitlement into the too-narrow "protected bike lanes" LAB promotes. LAB is a sham sellout.

You make good points but the rhetorical flaming doesn't do anything to improve your credibility. Principles apply to presentation and not only to content.