Bob Shanteau's "The Marginalization of Bicyclists"

Restoring Sensible Cycling Advocacy Series II of ?

Note on the Restoring Sensible Cycling Advocacy Series:

Platitude-driven activists have largely taken over sensible, principled cycling advocacy. Non-bicyclists tend to only see these individuals or their work and react swiftly to dislike many, if not most anything to do with cycling right off the bat. Actual cyclists, especially younger ones have been groomed by the propaganda and misinformation of platitude-driven dogma. History is even easier to forget when it’s obstructed or revised to fit a new narrative. This series seeks to repost and revisit some of the long lost or difficult to find writings made before the current activists parasitized the movement.

The following is long-form article written in 2013 by California traffic engineer (ret.) and bicyclist Bob Shanteau. It’s currently hosted over at the website iamtraffic.org - one of many legitimately resourceful sites for principled-driven cycling - but I wished to reproduce it here where it will hopefully get more visibility.

It’s a long article too - probably a 45 minute read and due to the graphics, it will likely be easier to consume on a larger screen such as a computer or tablet as opposed to a smartphone or within the Substack app.

However it’s an absolute must-read for anyone intersected in cycling whether they do the activity themselves or have a great disdain for it. If a reader here is the latter, hopefully by digging into this piece they can see just how far much of the bicycling movement has gone off the rails, and that there are at least a few bicyclists. If noting else you’ll know more about the issues than most bicyclists - including ones who are heavy in activism.

Shanteau’s work is also incredibly well researched with substantial footnotes. The quotes were verified and when possible the expired or lost URLs in the footnotes were updated. He draws most of them from old books and pamphletsgre which have been scanned to the web. Instead of quoting them by pasting the text as he did in his original piece, I’ve instead highlighted the scanned copies - usually with a red box or simply provided just a snippet of the text on the page.

Other than that, I’ve made a few emphases here and there usually bolding the text with some minor formatting to make the piece a bit easier to read.

Enjoy

How the car lane paradigm eroded our lane rights and what we can do to restore them

Not long ago I was riding in the middle of the right-hand (slow) lane on a 4-lane urban street with parallel parking and a 25 mph speed limit. I had just stopped at a 4-way stop when the young male driver of a powerful car in the left lane yelled at me, “You aint no f***ing car man, get on the sidewalk.” He then sped away, cutting it close as he changed lanes right in front of me in an attempt, I suppose, to teach me a lesson.

That guy stated in a profane way the world view of most people today: If you can’t keep up, stay out of the way. My being in the right-hand lane and therefore “in his way” violated his sense that roads in general and travel lanes in particular are only for cars, a viewpoint that I call the car lane paradigm. The car lane paradigm conflicts with the fact that in every state of the union, bicyclists have the same rights and duties as drivers of vehicles.

The car lane paradigm conflicts with the fact that in every state of the union, bicyclists have the same rights and duties as drivers of vehicles.

So which is it? Do bicyclists have the same right to use travel lanes as other drivers or not? Before lanes existed, bicyclists simply acted like other drivers. But now that travel lanes are common, most people grow up with the car lane paradigm with bicyclists relegated to the margins of the road.

This article goes into the history of how the car lane paradigm came to be and what we can do about it now.

Reading this is going to take a while, so here is an outline of where we’re going:

1897: In the beginning, bicycles were vehicles and bicyclists were drivers

1930: Bicycles are not vehicles

1911 – now: Lane lines are invented and become common

Oops, the inventors of lane lines forgot about bicycles

“Slower Traffic Keep Right” or “Slower Traffic Use Right Lane”?

What does the “or” in “right-hand lane or as close as practicable to the right” mean?

Do speed and might mean that travel lanes are actually “car lanes”?

1944: If you can’t keep up, you don’t belong (in the lane)

1968: Motorcyclists, but not bicyclists, are entitled to full use of a lane

1975: Bicycles once again defined as vehicles, but still not entitled to use of a full lane

Exceptions to the law requiring bicyclists to ride far right are better than nothing, right?

Now: No room on the road for bicycles

Bicycles at the far right and laned roads are incompatible

What do we do now?

1897

In the beginning, bicycles were vehicles and bicyclists were drivers.

In 1789, the United States Constitution delegated to the states the power of policing their own citizens, including the power to establish their own rules of the road. As it turns out, some states even allow local agencies to have their own rules of the road. Since it is impractical to go over the history of every set of rules of the road in the U.S., this article will for the most part focus on events at the national level.

As the bicycle became popular in the late 1800’s, some states and local agencies adopted laws prohibiting bicycles on their roads. By 1897 the League of American Wheelmen had successfully challenged those laws and declared in a pamphlet.

The League has made it possible for a cycler to ride the wheel on any street or highway in the United States. When the League was formed the bicycle had no legal recognition; now it is universally recognized as a carriage, and may travel with impunity wherever any carriage does. 1

Some foresighted people saw that it was necessary to formally organize the laws applying to road users into what came to be called “rules of the road.” One of the first places where rules of the road were adopted in the U.S. was New York City in 1903 2. In those first rules of the road, bicycles were defined as vehicles, the operators of which were treated the same as operators of other vehicles (most of which were horse-drawn wagons and carriages).

Many of those early rules of the road are familiar to us even today:

Drive on the right side of the road

Slower traffic keep right, overtake on the left

Don’t go faster than is safe

Turn left from the center of the road

Turn right from the far right, etc.

But there were variations in the rules of the road adopted by the various states and localities, which eventually led to an effort to create a model for the rules of the road for all the states and local agencies to follow. In 1926, the Uniform Vehicle Code (UVC) was created by what came to be known as the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Laws and Ordinances (NCUTLO).3 States are encouraged to adopt the provisions of the UVC as their own, with some complying more than others.

The original 1926 UVC incorporated the victory won by the LAW when it defined a bicycle as a vehicle:

For bicyclists, defining bicycles as vehicles was crucial, not least because two of the most important provisions of the UVC are the definitions of “highway” and “roadway,” which in turn use the term “vehicular travel”:

Notice that the definition of “highway” said nothing about speed, so the roads were just as open to the drivers of slower vehicles as to faster vehicles. That slower vehicles are normal was reinforced by the law requiring drivers of slower vehicles to keep right:

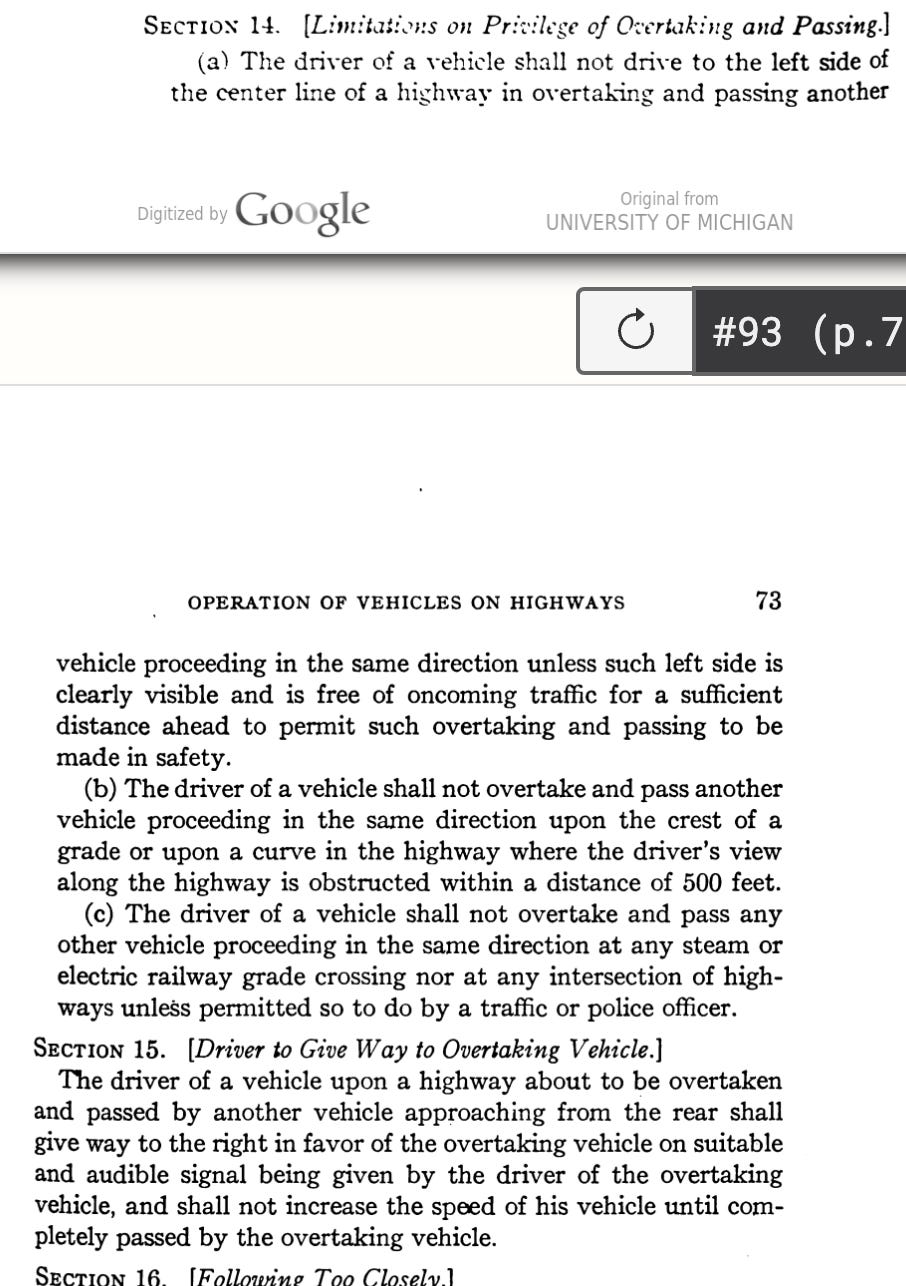

The UVC also addressed overtaking:

Except for the now antiquated rule about giving way to the right on an audible signal (which only makes sense on rural unlaned roads), the rules for overtaking are still well understood today, at least when it comes to motor vehicles overtaking other motor vehicles. Bicycles, however, are another matter. People don’t seem to understand how the rules apply when overtaking bicycles or being overtaken by bicycles. I believe the reason has to do with the car lane paradigm, which came about after the introduction of lane lines.

As it turns out, the overtaking law was written before lane lines became commonplace, so it is not surprising that it does not address overtaking on a laned road. Indeed, it is not logical for either the reference to the “right side of the roadway” or the requirement for the driver of the overtaken vehicle to “give way to the right in favor of the overtaking vehicle on audible signal” to apply on a laned road.

Without lane lines, a wide road has room for multiple lines of vehicles (as illustrated in the recently rediscovered movie of Market Street in San Francisco in 1906), so there needed to be a provision prohibiting moving left or right unless such a move can be made with safety:

Notice that even in 1926, the UVC authors assumed that all vehicles had a left side beyond which the hand and arm could be extended and that although Section 13b required only drivers of motor vehicles to sound their horns, Section 18a required drivers of all vehicles, including nonmotorized vehicles such as bicycles and horse drawn wagons, to sound their horns, too, even though nonmotorized vehicles were not equipped with horns. Thus the original UVC authors were apparently already thinking that all vehicles were motor vehicles, a viewpoint that still exists among highway and transportation professionals today. (note: also among many bicycle lane activists)

1930

Bicycles are not vehicles, but bicyclists have the same rights and duties as drivers of vehicles

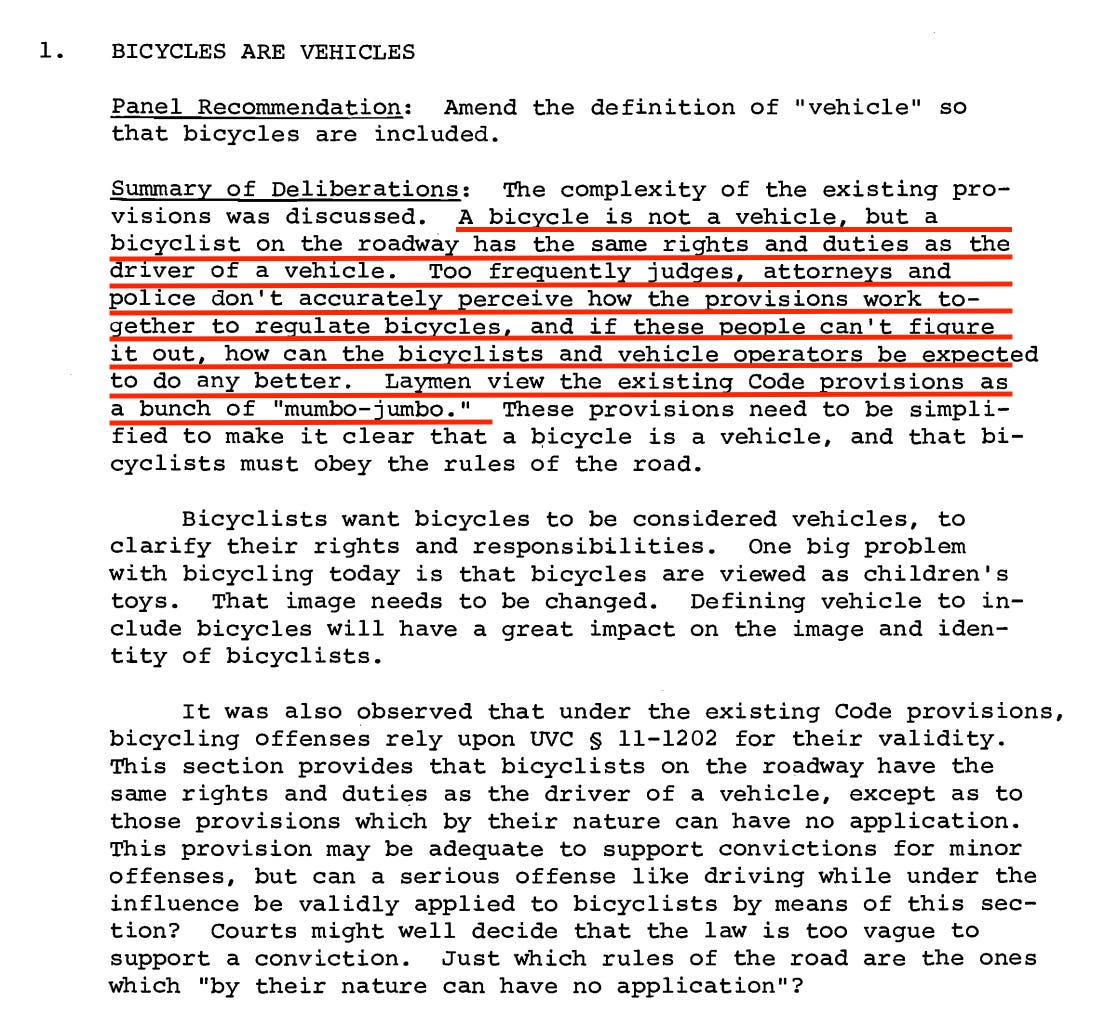

In 1930, the UVC authors decided that bicycles would no longer be considered vehicles and instead inserted a provision giving bicyclists the rights and duties of vehicles:

This seemingly innocent change had disastrous effects on bicycling. In 19754, the (National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances) NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws wrote (red underline):

Excluding bicycles from the definition of vehicles has been and is being used to justify the following inequities:

Police not preparing collision reports for bicycle crashes.

Highway engineers ignoring bicycles in the design of streets and highways.

Judges ruling that bicyclists are not intended users of highways, as an Illinois appellate court did.

Not treating bike paths as highways. This has led to treating bike paths as though they were walkways. For instance, instead of treating a location where a bike path crosses a street or highway as an intersection, with the same rules as a locations where a street or highway crosses another street or highway, a bike path crossing is usually treated as a crosswalk. Also, a California appellate court ruled that a bike path was equivalent to an unpaved walking trail, for which public agencies have immunity from liability for injuries of bicyclists caused by negligence of their employees in the design and construction of bike paths.

In his book, Fighting Traffic5, Peter Norton writes about how during the 1920s motoring interests fought and won a battle to define streets as spaces that excluded pedestrians, horses, streetcars, and bicyclists, writing:

"By 1930 most streetcar users agreed that most streets were chiefly motor thoroughfares."

Removing bicycles from the definition of “vehicle” was just one way of consolidating that victory.

Since bicycles were not motorized, they were not considered part of the normal movement of traffic.

1917 – NOW

The invention and proliferation of lane lines

As more and more motor vehicles were used on the roads, more rules were added and new road design features were created to regulate their operation. Although bicyclists often complain about stop signs and traffic signals, I believe that the one road design feature that had more impact on bicycling than any other was the lane line.

Today, lane lines are so common that it’s hard to imagine a time when they did not exist. But just like all other traffic control devices, they had to be invented.

The first documented use of a lane line was a center line installed on a rural highway in Michigan in 1911.6 In 1917, a center line was painted on Dead Man’s Curve along the Marquette-Negaunee Road in Michigan. That highway was only wide enough for two vehicles to pass, but there was a tight curve where drivers tended to cut the curve, resulting in head-on crashes. The line worked beautifully to keep drivers on their own side of the road, and by 1940 use of lane lines was common in the U.S., not only for center lines but also to designate multiple lanes in one direction.

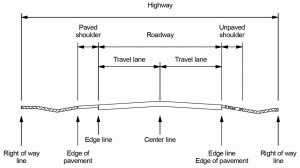

But what is a lane? Here is the dictionary definition7:

lane (n.)

A narrow passage, course, or track, especially a strip delineated on a street or highway to accommodate a single line of vehicles

Lane width is determined by the width of the widest vehicle likely to use the street or highway, which most often is a large truck.8 The current (2000) UVC contains the following provisions related to laned roadways:

1-147 – Laned roadway

A roadway which is divided into two or more clearly marked lanes for vehicular traffic11-309 – Driving on roadways laned for traffic

Whenever any roadway has been divided into two or more clearly marked lanes for traffic, the following rules, in addition to all others consistent herewith, shall apply. (a) A vehicle shall be driven as nearly as practicable entirely within a single lane and shall not be moved from such lane until the driver has first ascertained that such movement can be made with safety.

The requirement that a vehicle must be driven within a single lane means that a vehicle cannot occupy two lanes at the same time (except when changing lanes, of course). You would think that if one vehicle cannot occupy two lanes, then two vehicles would not be able to occupy one lane, but that’s not true. Some lanes are wide enough for two lines of traffic, such as where the lane lines are striped far enough apart for two trucks to travel side by side or where both lines of traffic consist of narrow vehicles. In such instances, a driver is expected to share a single lane side by side with other drivers (with the notable exception of motorcycles – see below).

Even so, because two cars or trucks cannot normally fit within a single lane, it is common for car and truck drivers to act as though they are entitled to a full lane. For instance, it is expected that a car driver who encounters a hazard in a lane (such as a rock) will swerve sideways within the lane without checking first for another vehicle in the same lane. And it is expected that the driver of a car or truck who encounters slower traffic will change lanes to pass.

Lanes work well to promote the orderly movement of traffic as long as all vehicles

Go about the same speed and,

Are wide enough that only one fits in a lane at a time.

Almost all motor vehicles can go fast enough to keep up, even on freeways, but some, such as motorcycles and motor scooters, are narrow enough to fit two or more side by side in a lane or to slip between lanes (called lane splitting). Even when the driver of a motorcycle or motor scooter uses a full lane, though, car and truck drivers have no grounds to complain because these smaller motor vehicles have enough power to keep up.

Oops, the inventors of lane lines forgot about bicycles

As a general rule, until lane lines were invented, bicyclists had the same rights and duties as other drivers. Just like any other vehicle, bicycles had to be driven on the right side of the road and, when slower than other traffic, had to keep right. A faster driver who could not overtake safely could honk, but if there was no place for the bicyclist to “give way to the right,” then the overtaking driver would simply have to wait until it was safe. Since most people underestimate the space a bicyclist needs for safety, the meaning of “keep right” and “give way to the right” is not always clear in the case of bicyclists.

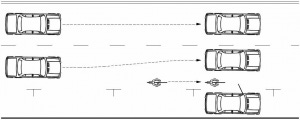

Because a bicycle cannot generally go as fast as a motor vehicle and because a bicycle is narrow enough that a motorist can often squeeze by one (unsafely) in a normal width lane, such behavior has become expected. Therefore most people do not believe that a bicycle is entitled to full use of a lane. The result is a mismatch between the historic concept of the bicycle as a vehicle and the basic idea of a lane’s being for a single line of vehicles.

I can find no evidence that highway engineers, law enforcement officers or legislators gave any thought to how bicyclists might use lanes during the time that lane lines were proliferating. It was apparently assumed that bicyclists would be relegated to the right edge of the road and that motorists would only move far enough left to overtake them, just as they had on unlaned roads. That assumption, though, failed to address a number of questions about how bicyclists and motorists were to interact on laned roads:

What happens when a lane is not wide enough for a faster vehicle to safely overtake a bicycle within the lane?

What happens when riding far to the right means being close enough to parked cars to be “doored”?

Is it acceptable for motorists to pass bicyclists without changing lanes?

Where on a laned roadway should a slower bicyclist ride?

Passing a bicyclist riding in the door zone puts the bicyclist in danger of hitting a suddenly opened car door.

Is a bicyclist prohibited from moving left or right within a lane without first signaling and checking to see if the movement can be made with safety?

The answer to these questions will be addressed in the remainder of this article.

“Slower Traffic Keep Right” or “Slower Traffic Use Right Lane”?

Recall that when all roads were unlaned, slower drivers were required to keep as close to the right edge of the roadway as practicable. With the introduction of laned roads, that law was revised so that slower drivers were only required to use the right-hand lane.

But all most people know about this basic principle is the highway signs that read “Slower Traffic Keep Right”. Even the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices9 (the bible of traffic engineering for installing signs and stripes) admits that the sign should be used where slower traffic is not using the right-hand lane:

The idea that the speed of traffic increases in the lanes furthest from the right-hand edge of the roadway is called lane discipline, and is formalized as follows (a similar provision regarding use of the right-hand lane first appeared in 1930 but was deleted in 1934 – the current provision was added in 194810):

The last sentence (which was added in 1979 through the work of Chuck Smith and the Ohio Bicycle Federation11) makes it clear that the reason for restricting slower drivers to use the right lane on laned roads and to drive near the right edge on unlaned roads is to facilitate overtaking and not, as commonly believed, for the safety of the slower driver. After all, overtaking drivers had always been prohibited from endangering the overtaken vehicle, whether the road had lanes or not. In any case, on a laned road the overtaking driver is expected to change lanes, which, because lanes are designed to be wide enough for the widest legal vehicle, usually means there is plenty of clearance between the two vehicles.

What does the “or” in “the right-hand lane or as close as practicable to the right” mean?

There has been a lot of confusion about what the “or” in UVC 11-301(b) means. Some people mistakenly interpret the “or” to mean “and”. By this interpretation, a narrow slow moving vehicle (such as a motorcycle) would have to be driven in the right side of the right-hand lane in order to comply with UVC 11-301(b), presumably in order to facilitate passing by faster vehicles in the same lane. Since the UVC specifically grants motorcyclists the right to use a full lane (see below), a driver could get a ticket for passing a motorcyclist without changing lanes. Therefore that interpretation must be incorrect.

A correct interpretation of the “or” in UVC 11-301(b) follows this line of reasoning:

The driver of a slow moving vehicle is in compliance with the law by meeting one of two conditions:

Condition 1: Operating in the right-hand lane.

Condition 2: Operating as close as practicable to the right curb or edge of the roadway.

On an unlaned road:

The roadway does not have a right-hand lane for traffic, so Condition 1 does not apply.

The roadway does have a right-hand curb or edge, so Condition 2 applies.

Therefore the driver of a slow moving vehicle operating as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway is in compliance with UVC 11-301(b).

On a laned road:

The roadway has a right-hand lane for traffic, so Condition 1 applies.

The roadway has a right-hand edge or curb, so Condition 2 also applies.

Condition 1 is less restrictive than Condition 2.

Only the less restrictive of the two conditions needs to be met in order to comply with the law.

Therefore the driver of a slow moving vehicle operating in the right-hand lane for traffic is in compliance with UVC 11-301(b).

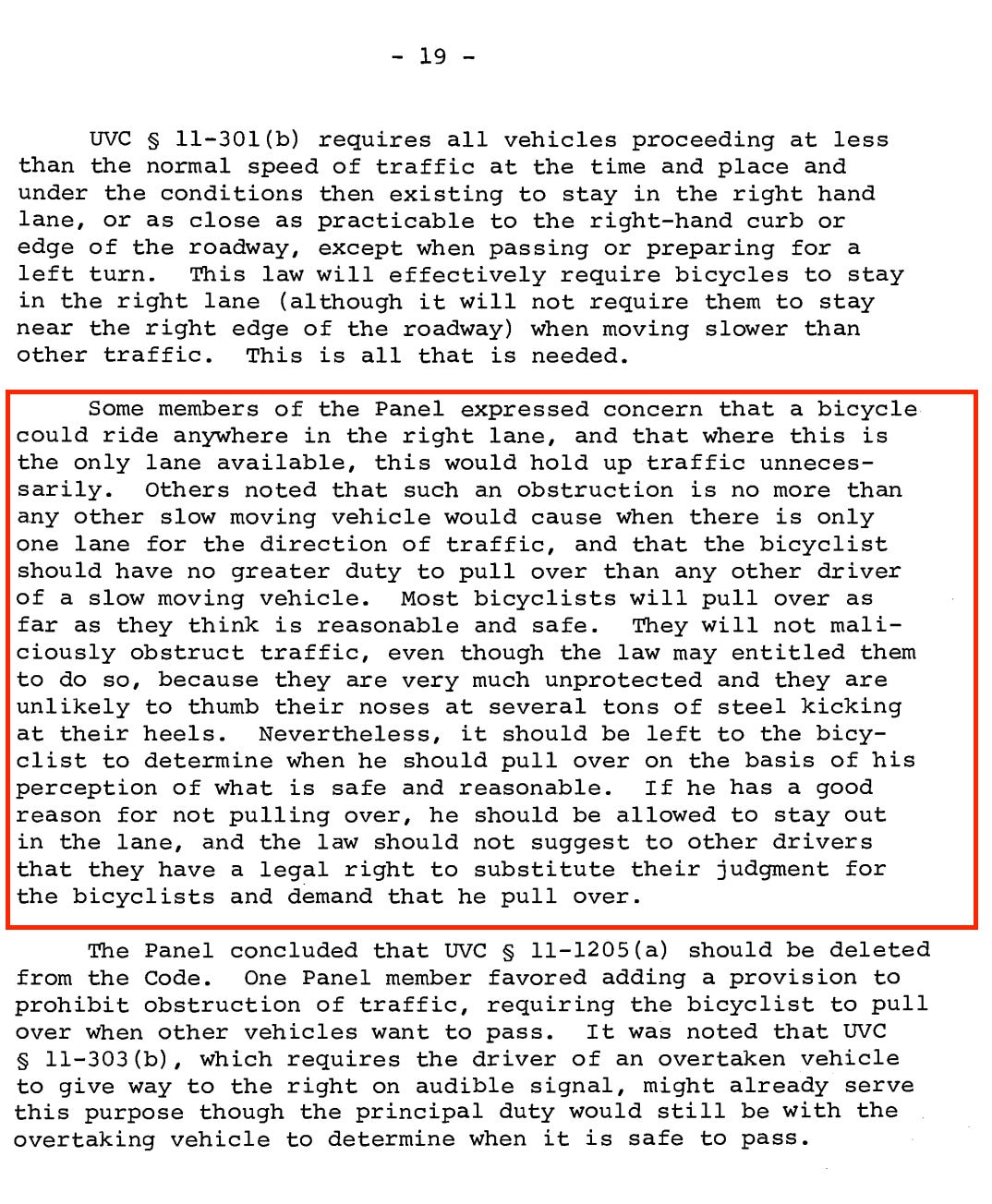

In 1975, the NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws came to the same interpretation when it considered what would be required of bicyclists on laned roads if the provision were deleted12:

Yet most people believe that it is OK to pass bicyclists without changing lanes, even when the lane is too narrow for a bicycle a vehicle to travel safely side by side. Also, people believe that cyclists are required to stay near the edge.

Why is that, and how does it affect bicycling?

Do speed and might make right?

Notice that UVC 11-301 (slower traffic use right-hand lane or as close as practicable to the right) says nothing about a minimum speed for the slower driver.

Before World War II, slow vehicles were still common on the roads. Deliveries of milk and other commodities in cities were still commonly made by horse and wagon. So any prohibition against driving too slowly would have to contain exceptions.

This law is commonly called the Minimum Speed Regulation. It was clearly not intended to prohibit slow moving vehicles from using streets and highways at all. For instance, at the time the provision was first adopted, trucks had solid rubber tires that prevented them from going as fast as cars. Now, technological advances allow trucks to go as fast as cars on level ground or downhills, although their limited power to weight ratio means that they still go slowly uphill. Clearly truckers going slowly uphill are not intentionally impeding other traffic, so the Minimum Speed Regulation is not applied to them. If it were, it would be tantamount to prohibiting trucks on uphill grades, which was clearly not the intent of the law.

Why is that same understanding not extended to bicyclists who, because of air resistance, are incapable of going as fast as cars on level ground? It is often assumed that because bicyclists are narrow they can get out of the way, and consequently that they must get out of the way.

Today it is virtually impossible to buy a motor vehicle that is incapable of going freeway speeds. That does not mean, though, that drivers of slower vehicles are no longer allowed to use the roads. In some places in Pennsylvania and Ohio, it is common to see Amish driving horse-drawn carriages. And Georgia’s Supreme Court found (Smith v. Lott) that the driver of corn combine going at its maximum speed of 15 mph was not violating that state’s Minimum Speed Regulation.13

(note the following quote is not cited in the original Marginalization piece, it’s instead been added for clarity)

“In my view a combine being driven on a road at a speed of 8 miles per hour or more is not an obstruction within the meaning of the statute so as to justify another driver who is traveling in the same direction to pass it in a no-passing zone. Under the majority opinion a slowly driven school bus could be an obstruction. More significantly, a school bus slowing down (or stopped) in order to make a left turn could be an obstruction.

This is not a case where the driver of the following vehicle came up behind a slowly moving vehicle, slowed down to its speed, followed it a short distance, and then decided to pass. Here the passing tractor-trailer was being driven by the plaintiff at a speed of 50 to 55 miles per hour. This plaintiff never slowed down; he just decided to pass in a no-passing zone at an intersection where the defendant planned to turn left. I would affirm the decision of the Court of Appeals”

In some states, the Minimum Speed Regulation omits the word “motor” and so applies to drivers of all vehicles, including bicyclists. In one of these states, Ohio, an appellate court found that a bicyclist using a full lane was not in violation of the law. The Ohio court (in Trotwood vs. Seltz14) compared the bicyclist to the corn combine in the Georgia (Smith v. Lott) case:

In both cases, the vehicle was being operated at, or close to, the highest possible speed. In either case, holding the operator to have violated the slow speed statute would be tantamount to excluding operators of these vehicles from the public roadways, something that each legislative authority, respectively, has not clearly expressed an intention to do.

Still, many bicyclists are even today being found in violation of the Minimum Speed Regulation, even though they were traveling at or near their “highest possible speed.” Clearly, the wording of UVC 11-804(a) needs to be clarified so as not to apply to drivers of vehicles going at or near their maximum speed. For instance, bicycle advocates in Ohio recently changed that state’s Minimum Speed Regulation to explicitly say that drivers of vehicles being operated at, or close to, the highest possible speed are not impeding faster traffic.

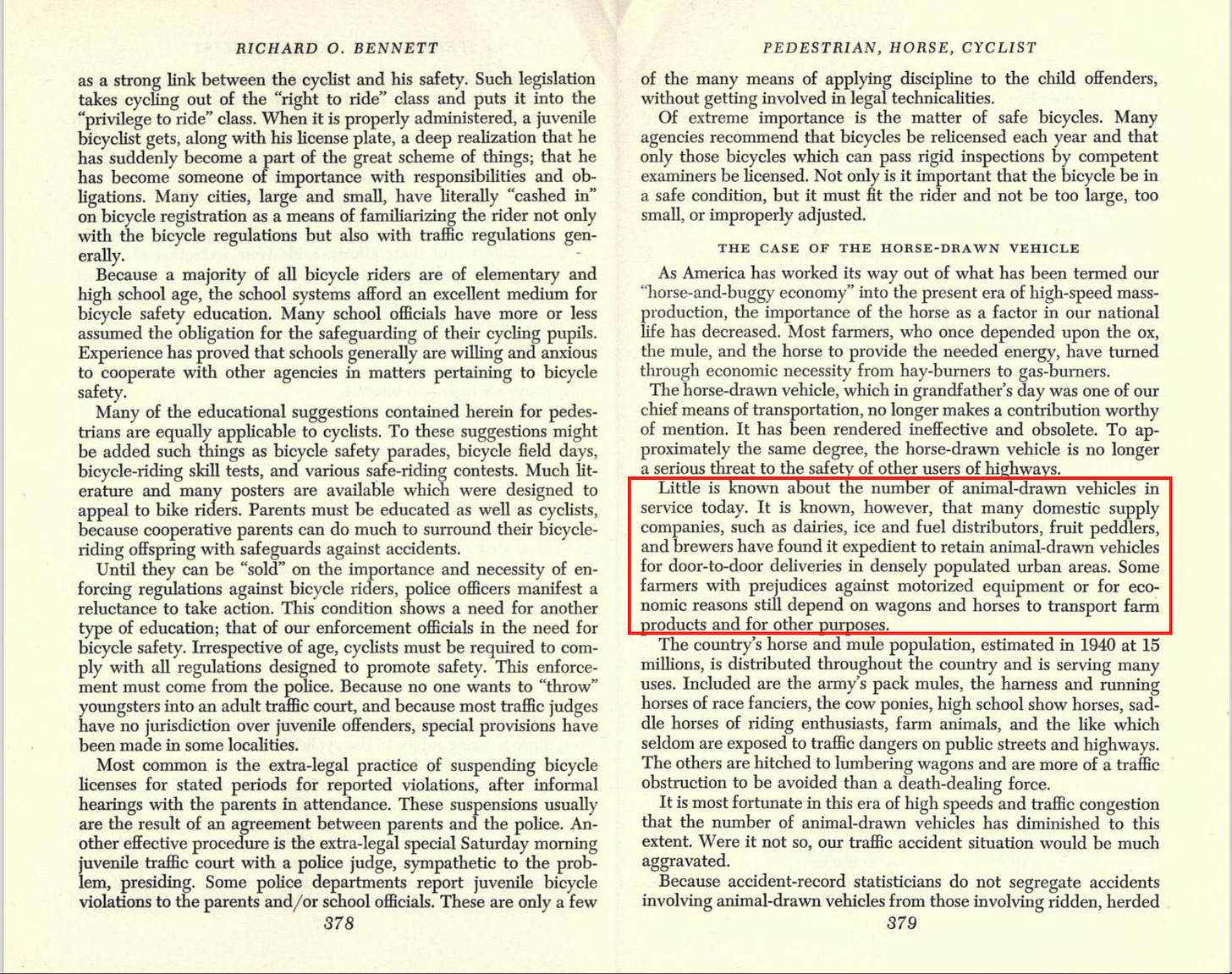

As time went on and roads became more congested and speeds of motor vehicles increased, the number of horse-drawn vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians decreased. Some highway professionals saw that as a good thing. For instance, in 1950, Richard O. Bennett of the National Safety Council said15:

(Note: In Shanteau’s original piece, both paragraphs proceed one right after the other. In the case of looking up the orginal text, that was not the case. In between each page is a fascinating section on just bicyclists starting on page 373. Separate post to follow on that one!)

Today, almost no horse-drawn vehicles use our roads. Pedestrians are accommodated on sidewalks along roads and crosswalks to cross roads. That leaves mainly bicyclists for modern drivers to resent. Where do bicyclists belong on modern roads, almost all of which are divided into travel lanes?

1944

If you can’t keep up, you don’t belong (in the lane)

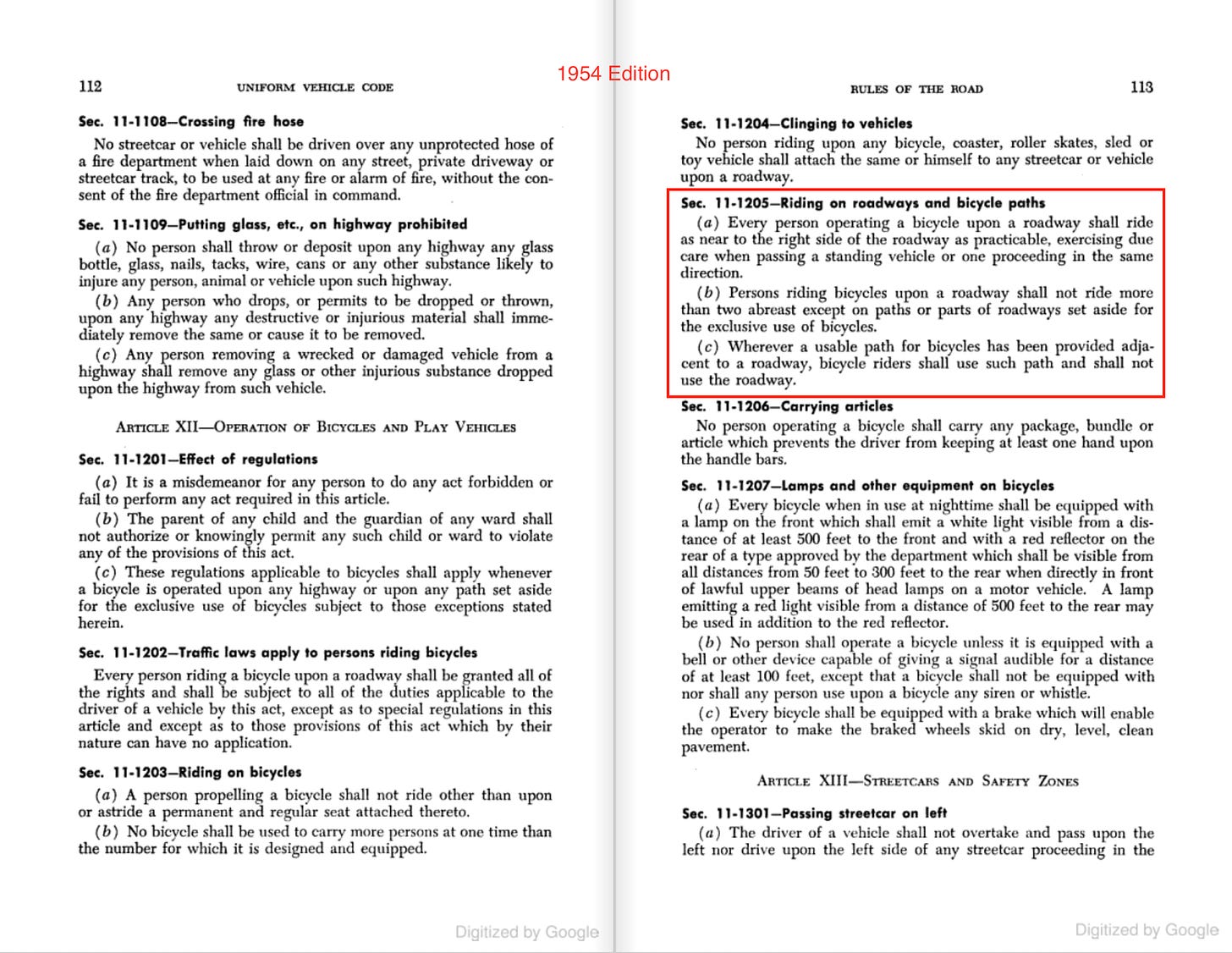

Until 1944, bicyclists on laned roads had the same lane use rights as other drivers. In that year, however, a new provision was added to the UVC requiring bicyclists to ride at the right edge of the roadway regardless of whether the road had lanes16:

(Note, in the original 1944 version, this is labeled as Article XI, Sec. 97. Sometime between revisions, the formatting of the UVC was relabeled, and re-numbered as Chapters and Sections for the 1954 edition)

I have not been able to find any background on this addition, but we can be pretty sure that no bicyclists were involved in the discussion. The end of World War II was still a year away, and most people who would have cared were either in the service or otherwise occupied.

For those of you have spent all your life under this law, this change might seem minor, but denying bicyclists the right to use travel lanes like other drivers is actually the biggest legal challenge to bicycles using roads that has ever happened in the US.

Notice the similarity between the wording of this provision and the second half of UVC 11-301(b).

The driver of a vehicle moving slower than other traffic has the option of either using the right-hand lane, or, if none, driving as far right as practicable. What UVC 11-1205 (Article XI, Sec. 97 in the 1944 version) did was to deny all bicyclists, not only those moving slower than other traffic, the option of using the full right-hand travel lane.

Basically, this law requires bicyclists to ride “Far to the Right” (FTR), even if the road has lanes. What the FTR law did was to create a third class of road user. Before, there had been only two classes: drivers and pedestrians. But now a new class of bicyclist was created, one without the rights of either drivers or pedestrians. The UVC had clear and well-understood rules for drivers and pedestrians, but bicyclists were treated like drivers of vehicles except they were denied the right to full use of travel lanes like other drivers.

The UVC therefore gave bicyclists the superficial appearance of being drivers, but without the right to use travel lanes like drivers. Although a travel lane is intended for a single line of vehicles, bicyclists were told that they could not use travel lanes like real drivers. Bicyclists were told they had to ride at the right edge and if they strayed from the edge, they were doing so at their own peril. Bicyclists were now officially second-class road users.

The UVC gives no reason for this new restriction on bicyclists, and I have been unable to find any from other sources. But what I have found about the FTR laws in a couple of states give clues. New York’s FTR law says that its purpose is to “prevent undue interference with the flow of traffic.”17

And when California adopted its FTR law (CVC 21202) in 1963, the California Highway Patrol (CHP), which sponsored the legislation, wrote a memo to the governor requesting his signature with this reasoning:

This will enable the development of a more effective safety program when the youngsters can see the simple and clear cut rules they are to obey.18

In effect, the CHP was saying that the ordinary rules of the road were too complicated for “youngsters” (there were virtually no adult cyclists at the time) to obey. In reality, the result of the new provision has been the exact opposite of being “simple and clear cut,” a fact that was illustrated in an educational film from the 1950’s warning children of the danger of riding next to a right turning car, inviting what came to be known as a right hook.

It was not until a large number of adults began bicycling during the “bike boom” of the early 1970’s that the actual effect of the new provision became clear.

In 1975, the NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws wrote19:

Despite the widespread misperception that it is dangerous for bicycles to mix with motor vehicles (as well as the desire to facilitate overtaking by faster traffic), what the proponents of this new provision apparently did not realize was that relegating bicyclists to the edge of the road increased the risk for the following types of crashes:

Right hooks

Left crosses

Driveway and intersection pull-outs

Sideswipes and rear ends during overtaking maneuvers

Door zone crashes

Road edge hazards

I was one of the new adult bicyclists who started bicycling during the “bike boom” of the early 1970s, and soon thereafter became involved in bicycling advocacy. During one of my first organized rides, I recall a group of us approaching a red traffic signal when one rider started to pass some stopped cars on the right. I distinctly remember a more experienced rider yelling, “Never pass a right turning car on the right!” That was my first exposure to the possibility that bicyclists need not expose themselves to unnecessary danger by hugging the curb.

1968

Motorcyclists, but not bicyclists, are entitled to full use of a lane

The NCUTLO took a very different approach to motorcyclists and travel lanes. On an unlaned road, of course, any driver, including a motorcyclist, who is traveling slower than other traffic is required to drive as far right as practicable. But since a motorcycle is narrow, the question arises about whether a motorcyclist is entitled to full use of a lane.

In 1968 the NCUTLO decided to grant motorcyclists the full use of lanes by adopting this provision20:

Lane position is important to motorcyclists – so much so that it is taught in training classes. Since many law enforcement officers are also motorcyclists and have undergone that training, they understand how important full use of a lane is for motorcyclists. These law enforcement officers know that it would be silly to expect a slow moving motorcyclist to use the right edge of the right lane.

The contrast with bicycles is notable. Even though bicycles are lighter and less robust than motorcycles, the NCUTLO believed that motorcyclists, but not bicyclists, should be entitled to use a full lane, meaning that bicyclists did not deserve the same protections as motorcyclists.

1975

Motorcyclists, but not bicyclists, are entitled to full use of a lane

In 1975, the NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws made two major recommendations: that bicycles be defined as vehicles and that the bicyclist-specific FTR law be repealed. The panel considered but rejected a proposal to extend the provision entitling motorcyclists to use the full lane to bicyclists. The full NCUTLO accepted the recommendation to define bicycles as vehicles but decided to leave in place the bicyclist-specific FTR law.

This was another disaster for bicyclists.

Due to the way the UVC had developed over the years, changing the definition of vehicle to include bicycles was not simple. Numerous other changes had to be made to provisions related to things like sidewalk bicycles, criminal and civil liability, etc. Perhaps due to the complexity of changing their laws, few states have followed suit, so little has actually changed as a result. Even in states that do define bicycles as vehicles, roads are still seen as motor thoroughfares and bicyclists as interlopers. That experience has made it clear that even though changes in the law are necessary for bicyclists to be seen as legitimate users of the road, such changes are not sufficient. It has been so long since bicycles were defined as vehicles that it will take a lot of effort for highway engineers, law enforcement officers, judges, and the public to see bicycles once again as vehicles.

The discussion among the panel members came down to these opposing viewpoints:

Unfortunately, during the meeting of the full NCUTLO in November 1975, the viewpoint opposing the deletion of the bicyclist-specific FTR provision prevailed.

The proposal to extend the provision entitling bicyclists to use of the full lane did not even make it through the bicycle panel:

So, the decision made in 1975 was that even though bicycles are vehicles, bicyclists themselves are not entitled to the same right to use of a full lane as drivers of vehicles are.

Exceptions to the FTR law are better than nothing, right?

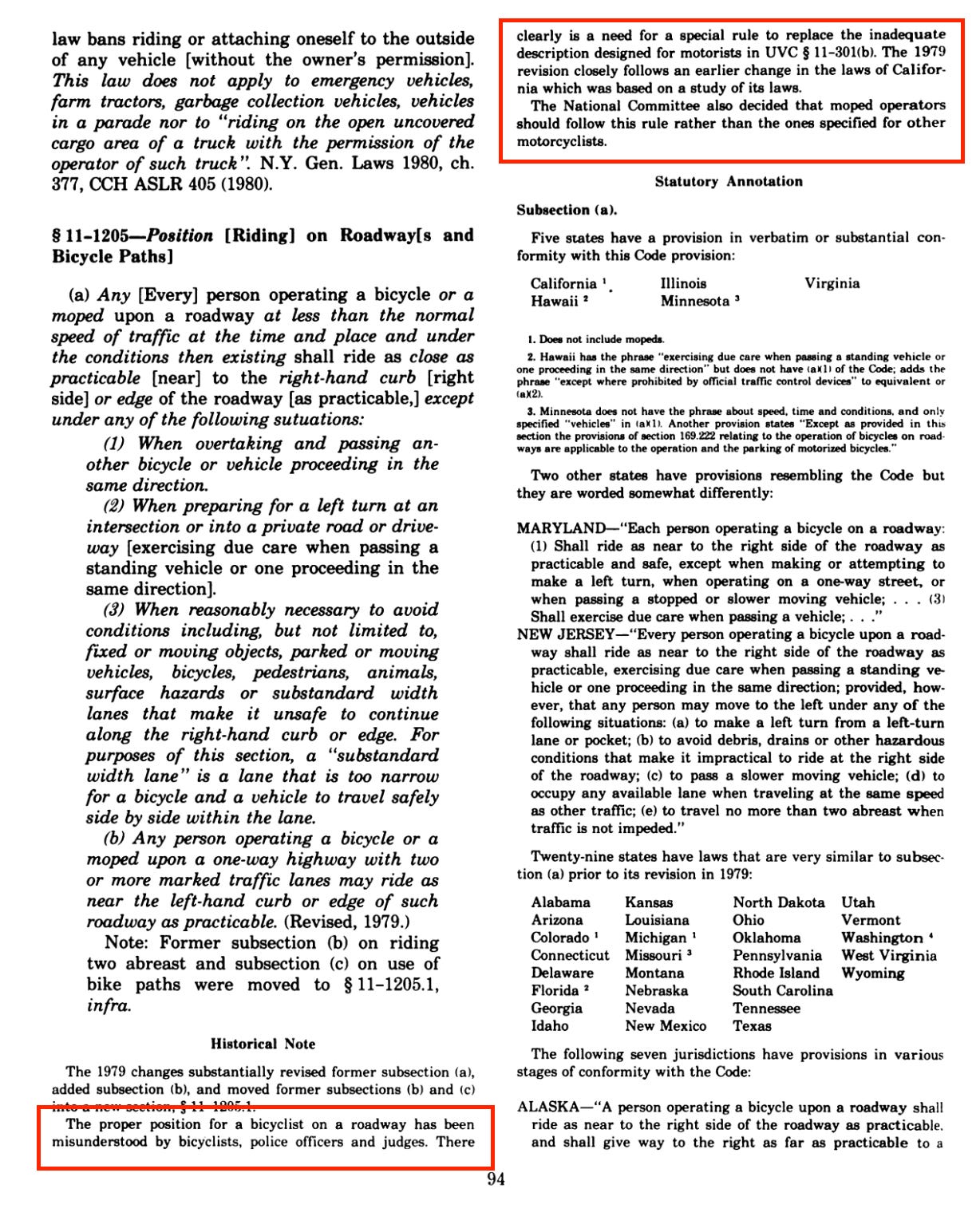

With the failure of the attempt to delete the bicyclist-specific FTR provision, attention next turned to clarifying what was meant by having to ride “as near to the right-hand side of the roadway as practicable”. In 1979, the NCUTLO decided to adopt amendments intended to clarify the FTR law. These amendments had originally been developed by the California Statewide Bicycle Committee in 1974 and became law in January 1976.

I was one of many bicycling advocates who took part in that effort. Our intent was to make it clear when bicyclists were not required to ride at the edge. Here is what we came up with:

UVC § 11-1205 – Position on roadway (a) Any person operating a bicycle or a moped upon a roadway at less than the normal speed of traffic at the time and place and under the conditions then existing shall ride as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway except under any of the following situations:

When overtaking and passing another bicycle or vehicle proceeding in the same direction.

When preparing for a left turn at an intersection or into a private road or driveway.

When reasonably necessary to avoid conditions including but not limited to: fixed or moving objects; parked or moving vehicles; bicycles; pedestrians; animals; surface hazards; or substandard width lanes that make it unsafe to continue along the right-hand curb or edge. For purposes of this section, a “substandard width lane” is a lane that is too narrow for a bicycle and a motor vehicle to travel safely side by side within the lane.

When riding in the right-turn-only lane. [Added in 2000.]

This time, the NCUTLO documented the reason for the change21:

The opinion that UVC § 11-301(b) is intended for motorists is a mystery, as the 1975 NCUTLO Panel on Bicycle Laws had clearly described the intent in its report.

Although the exceptions should have clarified the situations when bicyclists were not required to ride as far right as practicable, that fact is not well known. Until this year, for instance, the CHP Redi-Ref guide only mentioned that there were exceptions to the FTR law without actually listing them.22

And a police captain told me a couple of years ago that bicyclists can never “stray” from the right edge of the roadway. All across the country, bicyclists who do stray from the right edge of the roadway are being cited and convicted. Thus our efforts to lessen restrictions on bicyclists’ lane use rights failed.

Now

No room on the road for bicycles

Like millions of other children, I was taught to ride my bicycle at the right edge of the road. When I started riding seriously as an adult, I continued to ride the same way. I simply accepted the commonplace thinking that bicycles should not mix with cars and that I should stay as far from cars as possible. Thus when I started my bicycling advocacy, I remember thinking, “I need to do something about the fact that there’s no room on the road for bicycles.”

That attitude wasn’t always commonplace. When bicyclists won equal access to all roads in the 1890’s, they weren’t worried whether there was enough room on the road for bicycles. Since roads were built for carriages and wagons, every road had plenty of room for bicycles. All vehicles were governed by the same rules of the road, including the requirement for slower vehicles to be driven near the right-hand edge of the road. Bicyclists weren’t affected much by that law, since they were usually faster than the horse-drawn vehicles which dominated the roads at the time. But as motor vehicles became popular, bicycles went from being the fastest vehicles on the road to the slowest, and so were relegated to the right edge most of the time. But then, lanes were invented and shortly thereafter bicyclists were denied the right to use them. Despite the introduction of the exceptions to the bicyclist-specific FTR law, most people today believe as I once did, that bicyclists cannot stray from the right edge of the road. Indeed, most people believe that bicycles should never mix with motor vehicles at all.

With the exceptions added to UVC § 11-1205 being largely unrecognized, where are we? Edge riding leads to close passes (what some people call being buzzed), which is scary. And many crashes result between edge riding bicyclists and passing motorists, some leading to the death of the bicyclist. But bicyclists who ride in the travel lane are resented by motorists, who sometimes bully the bicyclist, as in my story at the beginning of this article. The danger of riding at the edge and the fear of bullying have made bicycling relatively rare in most places in the US. Most people believe, like I once did, that there is “no room on the road for bicycles”.

The reasons given for requiring bicyclists to ride at the right edge were bicyclist safety and to facilitate passing by faster traffic. Inevitably, as they got older, children stopped using bicycles for transportation and once they got a driver’s license, never bicycled for transportation again.

For their part, highway professionals in the U.S. never thought much about building roads to accommodate bicyclists riding at the edge (or anywhere else, for that matter). Their design vehicle was a large truck, but they gave no thought to how the roads would accommodate bicyclists. Today, roads are built as though they were motorways, with high speed limits, multiple lanes, widely spread intersections, and high speed merges and diverges. No wonder people believe that roads are for cars. Traffic law already requires slower drivers to use the right lane, but bicyclists don’t even have that right.

If a road has a paved shoulder or a bike lane or a sidepath or a sidewalk, then is a bicyclist who chooses to use a travel lane guilty of impeding faster traffic? A court in Texas found that a bicyclist using a travel lane on a high speed rural highway with what some people said was a “perfectly rideable shoulder” was guilty of reckless driving.23

Keri Caffrey and Dan Gutierrez have written:

Cyclists inadvertently, or forced by the combination of ill-conceived infrastructure and/or discriminatory laws, make it more difficult for motorists to do the right thing. The resulting conflict creates the animosity between cyclists and motorists with both thinking the other careless and stupid.24

Is the FTR law discriminatory against bicyclists?

When I ask this question of law enforcement officers, they insist that the FTR law is attribute-based, as though bicyclists were always slower than other traffic and that other narrow slow moving vehicles also had to drive at the right edge of the road.

But what other slow moving vehicles are there these days?

Horses have disappeared, and virtually all motor vehicles are capable of freeway speeds. What the law enforcement officers are expressing is a prejudice in favor of faster motor vehicles, and that because bicyclists are narrow and can safely (in their view) get out of the way, that’s what they must do in order to facilitate the movement of faster vehicles.

What the law enforcement officers don’t realize is that such FTR thinking is incompatible with the whole idea of travel lanes.

FTR thinking and laned roads are incompatible

FTR thinking permeates every aspect of bicycling on public streets and highways. What follows is a listing of what happens when bicyclists engage in FTR thinking:

Edge behavior

Overtaking slower traffic on the right

Creating two lines of traffic in one lane

Being hidden from opposing left-turning drivers

Inviting motorists to overtake without changing lanes

Inviting motorists to overtake on the left before turning right

Riding in the door zone where parking is permitted, otherwise in the gutter

Riding through surface hazards

Making left turns from the right edge of the road

Jumping onto the sidewalk and riding in the crosswalk to overtake stopped or slow vehicles

Infrastructure

Bikes May Use Full Lane signs

Shared lane markings (sharrows)

Share the Road signs

Bike lanes

Bike boxes

Two-stage left-turn queue boxes

Separated bikeways

Sidepaths

Education

Teaching children to ride FTR

Treating bicyclists as though they were incapable of learning or following the rules of the road for drivers of vehicles

Teaching people that being hit from the rear is the greatest danger

Thinking of travel lanes as “car lanes”

Thinking of roads as being intended only for cars

Enforcement

Citing bicyclists who stray from the right-hand edge

Citing bicyclists for delaying faster traffic

Forcing bicyclists who use a full lane to justify their choice

Failure to cite bicyclists and motorists for violations that are the major causes of bicycle collisions

Assigning fault for collisions to cyclists on the grounds that they were too far from the edge

Not assigning fault to motorists for going too fast for conditions

Not assigning fault to motorists for overtaking without enough clearance

Legislation

The bicycle-specific FTR law itself

3-foot passing laws

Making use of shoulders mandatory

Making use of bike lanes mandatory

Making use of sidepaths mandatory

Prohibiting bicyclists from roads that do not have separated bicycle facilities

If bicyclists don’t feel that they have the same right to use lanes as drivers of vehicles, then why should they feel like they have the same duties as drivers of vehicles?

That kind of rationalization leads to the following unlawful behaviors:

Riding the wrong way

Running stop signs

Not stopping for red lights

Not yielding to pedestrians in crosswalks

Not using lights at night

FTR thinking causes bicyclists to act like victims and not to be aware of how their own behavior affects their risk. Bicyclists don’t know what the real risks are or how to avoid them, leading to a misjudgment of the actual risks and to the following types of collisions:

Sideswipes

Right hooks

Left crosses

Drive-outs

FTR thinking distorts the way that bicyclists and motorists think of courtesy:

Bicyclists using travel lanes are viewed as being rude

Bicyclists see courtesy as being more important than their own safety

FTR thinking reduces bicyclist use of high speed or high traffic roads

FTR thinking leads bicycle advocates to:

Favor segregation

Refer to general purpose travel lanes as “car lanes”

Think of being pro-bicycle as the same as being pro-separation

Promote bicycle facilities that are inconsistent with the rules of the road for drivers of vehicles

Finally, FTR thinking has resulted in many, if not most people growing up with the belief that roads are for motor vehicles. Roads for motor vehicles do exist, of course – they are what Americans call freeways or tollways and Europeans call motorways. But FTR thinking causes highway engineers to treat conventional streets and highways (on which bicycle travel is explicitly permitted) as if they were motorways (on which bicycle travel is explicitly prohibited).

It is now generally accepted that if bicyclists cannot keep up, then both for their own safety and for the good of society they must either ride at the right edge of the road or on the sidewalk or bike path – or not at all. It is as if every street and road is a motorway, with the understanding that bicyclists are tolerated only as long as they stay out of the way of “real” traffic. The victory that the LAW celebrated in 1897 was for bicyclists to use the roads the same as other drivers, but once bicyclists were denied the right to use travel lanes like drivers of other vehicles, they were no longer a “normal” part of traffic.

What do we do now?

Suppose there were a law that required bicyclists to endanger and inconvenience themselves for the benefit of drivers in faster vehicles.

Well, there is such a law – it’s the FTR law requiring bicyclists to ride as close as practicable to the right edge of the roadway. And we do have bicyclists who accept that law and routinely ride much further to the right than is practicable. And we do have motorists and police officers and judges and legislators who see that system as just.

But there’s also a law that says bicyclists have the same rights and duties as drivers of vehicles. If drivers of other vehicles who are traveling slower than other traffic don’t have to drive at the right edge of the right lane, then why should bicyclists? That contradiction within the laws needs to be addressed.

The FTR law has led to a dysfunctional set of beliefs related to bicycling. Keri Caffrey writes:

Beliefs are the number one impediment to cycling. The belief that it is too dangerous. The belief that it is too difficult. The belief that human beings driving different types of vehicles can’t coexist on unadulterated roads.

The belief was created by motordom in the 1920s, has been the dysfunctional doctrine of “safety material” for almost a century, and now is being perpetuated by shortsighted bike advocates in the name of getting more asses on saddles25.

The FTR law needs to be repealed in order to once again give bicyclists the same rights and duties as other drivers. Unfortunately, since that law has been on the books longer than most of the readers of this article have been alive, most people see the law as normal and reasonable. But it is not. It is the result of the mistaken idea that bicyclists cannot control travel lanes. Not only is the idea that bicyclists cannot or should not control travel lanes responsible for the FTR law, it is also responsible for low mode share. FTR thinking leads to the belief that bicyclists controlling travel lanes is somehow rude or more dangerous than riding at the edge of the road or on the sidewalk.

Along with repealing the FTR law, we need to encourage cities, counties and states to design roads and to install traffic control devices that recognize bicyclists as having full lane use rights. Instead of designing only for fast motor vehicles, highway engineers need to design streets and highways for a variety of speeds. On all streets and highways where bicycling is permitted, we need squared-off intersections that encourage motorists to drive more slowly and yield to bicyclists instead of high speed ramps that discourage yielding to slower bicyclists. Instead of the Share the Road sign, we need to expand use of the Bikes May Use Full Lane sign. Instead of shared lane markings (what some people call sharrows) in the gutter or in the door zone, we need them in the middle of the lane.

Also, along with repealing the FTR law, we need better education. For instance, instead of telling children to stay out of the way of cars, we need to teach them how to interact with motorists as drivers of vehicles. By teaching school children how to drive their bicycles in traffic, they will have a jump start on learning how to drive cars better when they grow up.

But the first step is repealing the FTR law. As long as the FTR law is on the books, bicyclists will continue to be marginalized and denied full lane use rights.

Court Decisions, Legal Opinions &c. regarding the Rights of Cyclists in Streets, Parks, &c., League of American Wheelmen, Boston, 1897. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

William Phelps Eno, Street Traffic Regulation, The Rider and Driver Publishing Co., New York, 1909. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Uniform Vehicle Code, National Conference on Street and Highway Safety, Washington, D.C., August 20, 1926. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Report of the Panel on Bicycle Laws and Supplementary Agenda for the Subcommittee on Operations, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., January 27, 1975. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Peter D. Norton, Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City , MIT Press, 2011.

Inventor of highway centerline receives international honor, Michigan Department of Transportation. retrieved via Internet Archive 15/4/2023.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language , Fourth Edition copyright ©2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Updated in 2009. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

A Policy on Geometric Design of Streets and Highways, Sixth Edition, American Association of Street and Highway Transportation Officials, Washington, D.C., 2011 [Unable to verify, I sold my copy years ago]

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C., 200 [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Traffic Laws Annotated, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., 1979. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Fred Oswald, Ratings — Local Bicycle Traffic Ordinances. retrieved 5/7/2012. [Updated to Internet Archive version from era due to domain name expiration, 15/4/2023]

Traffic Laws Annotated, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., 1979. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Smith v. Lott, et al., Georgia Supreme Court, 1980. retrieved 6/2/2013, [Original link dead, updated with alternative website 15/4/2023.]

Trotwood v. Selz, Court of Appeals of Ohio, Second District, Montgomery County, 2000. retrieved 6/2/2013 [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Jean Labatut and Wheaton J. Lane, eds., Highways in our national life; a symposium, Princeton University Press, 1950 . http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/jean-labatut/highways-in-our-national-life-a-symposium-hci/page-38-highways-in-our-national-life-a-symposium-hci.shtml retrieved 5/7/2012 [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Note: In Shanteau’s original piece, both paragraphs proceed one right after the other. In the case of looking up the orginal text, that was not the case. In between each page is a fascinating section on just bicyclists starting on page 373. Separate post to follow on that one!

§ 1234, Laws of New York, http://public.leginfo.state.ny.us/LAWSSEAF.cgi?QUERYTYPE=LAWS+&QUERYDATA=VAT1234. retrieved 5/12/2013 [site dead]

Memo from CHP requesting that Governor sign AB 1296, May 9, 1963. [unable to find such note however similar claims are made in “The Slow Cyclist Political Problem: the California Highway Patrol’s Policy of Motorist Supremacy” by John Forester.]

Report of the Panel on Bicycle Laws and Supplementary Agenda for the Subcommittee on Operations, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., January 27, 1975. retrieved 15/4/2023. [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Traffic Laws Annotated, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., 1979. retrieved 9/17/2011 [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Supplement to Traffic Laws Annotated, National Committee on Uniform Laws and Ordinances, Washington, D.C., 1979 [confirmed online 4/14/2023]

Redi-Ref, California Highway Patrol, Sacramento, CA, various years [unable to confirm]

Cycle Dallas: Reed Bates found Guilty of “Reckless Driving”. retrieved 5/12/2013, original link dead, similar story reported here

Private communication, November 4, 2012 [unable to confirm]

Private communication, May 16, 2012 [unable to confirm]